Station/Museum

The Railroad Station Ticket Validator

First-time visitors to the ATT&NW are often impressed by the attention paid to preserving the "details" of railroad history, large and small. The roundhouse and turntable are striking examples, along with many of the wayside signals, restored and in full operation along the line.

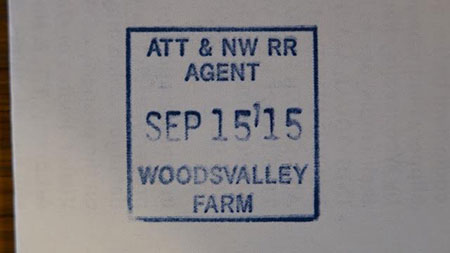

Look carefully and you will notice smaller, less-obvious pieces of history. On the first floor of Woodsvalley Station, atop the massive safe once used by John Woods’ grandfather, Woodson K. Woods, visitors might notice a heavy device that looks like an overgrown stapler.

This is a Cosmo Model 2 ticket validator, an example of the most popular ticket validator ever used by transportation companies, and an early model of the last such device produced in North America. These were commonly found in every railroad station and ticket office in North America.

The ticket validator was the most important piece of equipment in any railroad station, because it represented the formal "signature" of the railroad company in all business matters. Every ticket sold, check received or official document generated by the station agent had to carry the dated imprint of the ticket validator as proof of authenticity, sale or receipt. The unique "thud" sound of the agent validating tickets echoed through the lobby of every American train station.

The validator consists of two important parts: the validator machine and the die.

The validator, made of heavy cast iron and sitting on thick rubber "feet," contains a striking knob, an ink ribbon and a set of changeable date wheels. One of the first jobs on a ticket agent’s shift was to set the date wheels to the day's date. In busy offices, the agent would put on rubber gloves for the messy job of changing the ink ribbon every few months.

The die is a piece of carefully machined bronze, engraved with the station name and the name of the railroad, in reverse. Smaller stations had one validator and one die. At larger stations, or in stations where there were multiple agents working in shifts, and many validators in use, each agent had his or her own die, with a letter or number corresponding to the person to whom the die was assigned. So important were the actual dies, that they were locked in the station safe when not in use. In many cases, the dies were destroyed if the station closed or railroad ceased passenger service. In a few cases, the dies were presented to retirees as "gifts" or were sold or given to collectors who sought them. Many of those were "squirreled away" and have only emerged as collectibles in recent years. Today, railroad station validators, with dies, are highly-prized pieces of railroadiana.

The ticket validator was a forerunner to other marking devices, including the rubber stamp, and has a history dating back to the Civil War, when a marking device was needed to validate the revenue stamps used by the Union to finance the war. Counterfeit stamps were rampant, and the first brass-wheel validators showed up in government offices, with the railroads quickly following the practice. Many other businesses and government agencies used similar devices for establishing validity of documents.

This ATT&NW dater actually served for many years in the St. Louis city ticket office of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad before it was acquired by a collector. The ATT&NW die was manufactured by the company in Massachusetts that still owns the patents and designs for the Cosmo dater, still in limited use by various entities. The validator and die were presented by Dave and Dan Busse as a Christmas gift to John R. Woods following the completion of the ATT&NW station.

Cosmo ticket validators just like the one on the ATT&NW were used in bus stations, airports and other transportation offices well into the 21st century, until the wide use of computer-generated ticket printers and e-ticketing made them unnecessary.